115 - Schnellzughöhle

Schnellzughöhle was discovered in 1980, a draughting, horizontal passage which ended in a choke (with some survey cotton found). This was dug and a complex abandoned system reached via a bolted climb. The limit of exploration was a ramp which led both up and down to undescended avens at -80m. The size of the passage and strength of breeze made a return very attractive.

The initial rigging in and pushing trips did not follow the marathon-from-the-word-go pattern of the Stellerweg heroes; usually two 2-man teams would descend in relay each day. This avoided the withdrawal symptoms and 'driver of the year' risks associated with all night trips.

Rigging in to the 1980 limit took one trip, the old bolts were reused. An inlet above the ramp was also explored; a series of 8 cascades led up 30m to a choke. At the aven a decision was made not to descend via the main shaft but to a rift to one side. This was primarily because a pile of loose boulders threatened to mangle anyone dangling below. Also, a peer into the depths showed that rebelaying would be necessary, giving no advantage over the rift. The rope dropped via a series of muddy ledges (although there were no severe cam-slipping problems) into a small active streamway, just a tiny dribble when it wasn't raining. Two fine, clean-washed pitches of 19m and 14m followed, which were the scene of an exciting trip when it did rain once. A tremendous whooshing noise announced the arrival of quite a small flood pulse, which would have made the pitches miserable rather than impassable; the intrepid explorers were exiting too rapidly to actually prove this. The second wet pitch was followed by a damp 9m ladder climb to a 15m by 5m ledge. Here the water disappeared into boulders, and then a 34m freehang dropped into a chamber.

This was big, 30m by 30m with the roof beyond stinky range. A food dump was established here, complete with stove in case the pitches ever did become impassable. A stream vanished into an uninviting slot in the floor. Upstream, 60m of big phreatic tube connected with another aven. Downstream, a similar 5m diameter tube was reached by traversing up through boulders from the stream bed. It proved too difficult to follow the stream at high level (this had also been found out by a rather forlorn, green bat here found entombed). However, 50m from the chamber the tube branched off into a phreatic maze. The draught was pursued to a second stream, and a small cairn built. This was later to be found by the Stellerweg team.

Meanwhile the streamway was pushed. It meandered on and on for 800m, and required much shuffling and a couple of awkward traverses. An hour of this led to a more comfortable sized streamway (probably the Stellerweg water). This proceeded with a 7m lined climb to a sump.

This was easily bypassed via a 3m diameter phreatic tube which emerged above the stream again. The discovery was celebrated by a severe attack of the Lurgi and an epic 11 hour exit, after which the narrow streamway was christened Pete's Purgatory. A ladder was rigged back to the stream, and the descent continued with increasing enthusiasm. The canyon was 1.5-2m wide, too high to see the roof and getting bigger all the time. Fifty metres and a 5m ladder climb led to 500m of fine stream, which descended quite rapidly by numerous sporting cascades.

A 5m pitch (the 'twelve foot climb') was reached and bolted when play was stopped again by Lurgi. The victim escaped this time, but his partner got lost near the entrance and had to be rescued the following morning. 500m after the short pitch came a 10m wet pitch and then 300m more passage. In two places here, classic vadose canyon gave way to low, wet ramps with some grotting in boulders. A fine, free-hanging pitch of 10m then dropped into a dark pool. 150m more stream, and a 15m pitch, broken by a ledge, was followed by a 4m roped climb. 70m of horizontal passage followed, with dismal pools leading to hopes of a sump; these were dashed by another pitch, a dry 15m free-hang. The streamway continued inexorably to yet another 10m pitch, but a realistic decision / miserable witter was made and the derig commenced to the sump bypass. This was completed in a mammoth 3-wave session, remarkable for feats of gluttony and nicotine consumption, and an attempt to wall in the consultant geologist and catering manager.

Trips into the lower streamway were becoming quite serious, with hitch-free trips taking from 12-14 hours, typically adding just a couple of bolts. Flooding could be an extremely dangerous proposition: there is nowhere warm and dry to hide. However, it needs a good survey and the combined system is getting close enough to the 700m mark to put a return next year very much on the cards.

Simon Kellet.

UBSS in Austria - Stellerweghöhle and the connection

Stories of pitches, classic continental rigging and depth, honour and glory attracted the UBSS to join CUCC in Austria. With them came the state of art tackle they had bought to the keen specifications of their more experienced members. The latter came too, though not all of their experience had been of caving over the previous few years. One, a Doctor noted for his energy, sent out to buy an escort for transport, misinterpreted his brief and provided a racy little sportster. The others showed good humour by providing the real transport; an Escort advertising longevity and the redundancy of prissy bodywork, and an Imp with a trailer its own size. The trailer was in quite reasonable repair. Your correspondent provided a tent suitable for the bridge parties and a cook to double as decoration and baggage for the sportster.

The walk to Stellerweghöhle (41a) takes a contoured path from the restaurant overlooking the campsite. In the sun it is an enjoyable stroll made serious only by the thoughts of caving ahead. Memories of the long slog across the plateau on previous trips are recounted with expansive gestures over the skyline, and just a hint of 'hard days remembered' in the eyes. The easy efficiency of our path soon leads to an orange paint blob marking the start of the winding climb up through thick bush and stone gullies to the 41a entrance. Below, a more serious slither leads down to 115. The entrance belches cold air, welcome relief to sweat for just a moment before the various chills of present, past and future cool the mind.

The route to the big pitch follows phreatic passages developed along inclined bedding planes. It is crossed by 45 degree ramps which are traversed, several with the aid of fixed lines. The first pitch bypass takes one of these ramps down, then along the strike to join the bottom of the pitch chamber. The final ramp is descended, dropping down the base of its 'T' section, then over large boulders to the division of the rift. To the right last year's route gains an airy take-off made horrid by mud and spoilt further by rebelays at several contact points. To the left, a couple of 10m abseils lead to a fine free hang for the big pitch: a splendid 100m drop, hanging at times at least 10m from the nearest wall, broken only by a free rebelay in slings.

At the foot of the pitch a stream runs down the rift, then below an awkward traverse section which is followed by a series of progressivly wetter and tighter pitches. We remember the sound of flood pulses, a feature not to be taken lightly in a place with the promise of this cave. A hammered squeeze on a 6m pitch adds interest as a marker of better to come - not the least interest is the thought of others negotiating it. Strange Comfort. An awkward 7m pitch then a thrutchy climb (up over large boulders and losing the water) folows the rift into a magnificent cleft some 3m wide and over 100m high. Oddly it was at this spot last year that we directed attention to an alternative route (the 'German Route') for 3 days, pushing to -140m in increasingly nasty sharp, tight passage. Odd how that narrow rift quietened enthusiasm with such a superb way lying ahead.

The route on follows the now dry rift and includes numerous small pitches and traverse rebelays. The water is rejoined and the passage roof closes to within 10m in places. The final pitches are in clean washed round pots with a stream lip and more spray from above. The walls are decorated with the fossils of large bivalve molluscs about 30cm across. The rift must surely plunge on down, grey and businesslike, and deep.

Here, on our third major rigging-in day, we placed a final bolt ahead of last year's progress. We had consolidated the route with fine rigging in preparation for the pushing trips beyond. Each trip had been tiring to the experienced members, now we were damp as well and still the return to make. During the ascent one wondered what one was doing here; building character or the foundation of more good stories ? Certainly we had provided the basis for a memorable through trip as the next visit revealed. We even lured the 115 contingent down to this spectacle of fine cave and tasteful rigging and the through trip gave us the opportunity to curl a lip over the 115 entrance series.

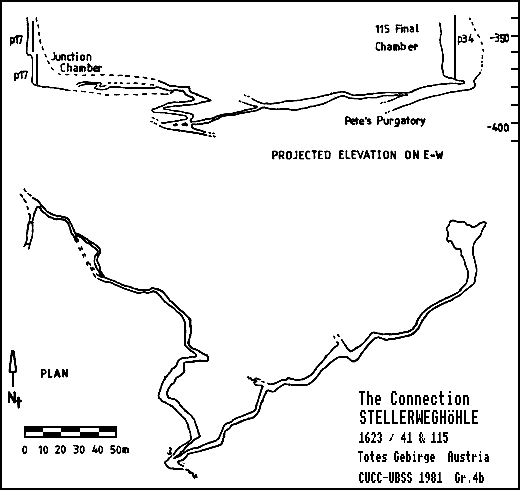

The last pitch drops into Junction Chamber. Turning right one follows a gently descending stream. Soon the way traverses the rift above the stream. Above (after 40m) a hole in the roof leads to a series of small and dusty tubes. We are in a phreatic zone. After a few bends the passage on closes down to a short flat out crawl regaining the stream. More traversing on dusty loose mud ledges in the passage roof gains a hole in the roof and a series of phreatic tubes of railway tunnel proportions. These tubes can be followed back to Junction Chamber entering about 10m above the floor. Ahead they take a series of swooping inclines punctuated by dramatic bends. This area was much appreciated by the surveying party. A final incline to a sharp left bend regains the stream in its rift and reveals the sight, surprising to the first explorers, of a cairn.

From this lowest point of the connection there are two routes on - one a traverse over the stream then a climb over large boulders into a passage entering from the left; the other a 0.75m hole at floor level to the left of the start of the final incline. The two ways join in an uphill sandy passage (1.5m high by 3m wide).

At some stage one should appreciate the significance of the cairn - marking the limit of exploration of a side line in 115. The eagerness to get out through 115 may have reduced interest in 41a, a shame as it was only later that we looked at another exit from Junction Chamber. Anyway, following the uphill passage one can reflect on the peace of this area, the comfort and ease of progess. A nice site for a bivvy if necessary.

Next a flat out crawl hardly slows progress into the teeth of a healthy draught. Enthusiasm is rewarded by a motorway (almost) sized passage (all things, the educated mind realises, are relative. John Parker once described a passage: "It's huge in places, one can stand up even." This passage really is big). Now turning right - who knows what lay to the left - a further 90m of phreatic tube led to the 115 main passage.

Our next interest in 41a lay in derigging it. This came after a suitable period for through trips of both a caving and an enteric nature - which some of our party combined.

At Junction Chamber we noticed the obvious and hitherto ignored 15m climb leading left into a choice of phreatic passages with further avens gaping above - a really large junctional complex. To the right after 50m the passage led to a rift above a stream. The other choice was a large phreatic tube (10m by 10m) in which easy progress down a 30 degree slope gained 50m of depth. This scramble down boulders leads to a cross-rift after about 150m. To the right a stream, to the left a traverse after a short distance. It is galling to find such a passage on your derigging trip, but that's why the description stops here.

Steve Perry

- Logbook

- BCRA Caves & Caving Report

- Cave Development in the Totes Gebirge (from CU Report)